I spent my entire afternoon at the Musée international de la Croix-Rouge et du Croissant-Rouge. The ICRC is one of the few organizations whose efforts I stand behind fully. Apart from supporting them monetarily, I did some work with them while in Gaza some moons ago. At the time, the Director was Mustafa Abdelshafi, one of my grandfather’s best friends, always gentle and gracious, now resting in Light where there is no need for organizations such as the ICRC.

I spent my entire afternoon at the Musée international de la Croix-Rouge et du Croissant-Rouge. The ICRC is one of the few organizations whose efforts I stand behind fully. Apart from supporting them monetarily, I did some work with them while in Gaza some moons ago. At the time, the Director was Mustafa Abdelshafi, one of my grandfather’s best friends, always gentle and gracious, now resting in Light where there is no need for organizations such as the ICRC.

Of all of the museums to which I have been, this was by great measure the most interactive, and the most emotionally challenging. Four very poignant sections. The first, a wall of faces. Very young children lost to their families after the Rwandan genocide.

A photo tracing initiative intended to help reunify thousands of children with their families. Due to both their age, and the trauma which they experienced, it was very difficult for the children to identify their families or to properly contribute to this effort. Instead, the ICRC worked with UNICEF to photograph each child and compile their information into a database. Albums were then distributed to camps for refugees, the displaced. The project extended from 1994 until 2003, and saw the reunification of approximately 20,000 children.

Second, a small confined space in remembrance of the Srebrenica massacre. Over the course of several weeks in 1992, the Serb military massacred over 8,300 Muslim men. One of the many war crimes committed by the Serb army, this one hits a slight more close to home because these massacred men are my brothers in Faith. Among the other war crimes committed by the Serbs was a systematic raping of all women, ages ranging from the infant to the elderly; I would have been subjected to such assault had I been born in that part of the world, rather than belonging to Palestine (to which a different sort of trauma infliction exists).

Second, a small confined space in remembrance of the Srebrenica massacre. Over the course of several weeks in 1992, the Serb military massacred over 8,300 Muslim men. One of the many war crimes committed by the Serb army, this one hits a slight more close to home because these massacred men are my brothers in Faith. Among the other war crimes committed by the Serbs was a systematic raping of all women, ages ranging from the infant to the elderly; I would have been subjected to such assault had I been born in that part of the world, rather than belonging to Palestine (to which a different sort of trauma infliction exists).

Third, what the Museum calls ‘Witnesses’, recordings by individuals who were helped by the ICRC. I wish I could tell you that I listened to all, that I was a witness to their pain, but that would be a lie. I could barely make it through three and found myself bawling. I did not have the emotional energy to go beyond this, today.

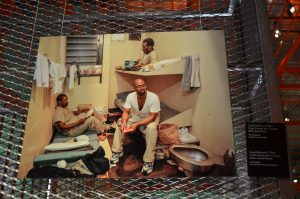

Finally, their temporary exhibit about the prison systems. Aside from a few English errors in their translations, this exhibit came at the end of my hours-long touring and I could not make it through the entire thing. It was simply too much for my tiny heart.

I do not believe that incarceration rehabilitates, and I believe that near all are possible and worthy of rehabilitation. I am also far too well versed in the racial and monetary motivation of the prison industrial complex, and so today, this experience near broke me. You are forced to walk through cells, the lights are far too bright, and there is a noise component to the exhibit. This museum translates onto its visitors exactly what a humanitarian crises does to those on whom it directly inflicts pain – it displaces you.

An interesting theme throughout the Museum was the impotence of the UN to intervene, though they were aware of the atrocities occurring. Though this is something of which I am aware because I pay attention to humanitarian work and crises, it was interesting to see it so glaringly the case in this city, directly across the street from the United Nations itself. Which is where I went to next, and how I wasted one hour of my life which I will never get back.

An interesting theme throughout the Museum was the impotence of the UN to intervene, though they were aware of the atrocities occurring. Though this is something of which I am aware because I pay attention to humanitarian work and crises, it was interesting to see it so glaringly the case in this city, directly across the street from the United Nations itself. Which is where I went to next, and how I wasted one hour of my life which I will never get back.

The history of the UN I studied extensively in university. While the Universal Declaration of Human Rights is an extraordinary treaty, the UN is not today what it was originally; in great part, and as so many other organizations of its standing eventually become, it is highly corrupt and a tool of the powerful, to the extreme detriment of the already weak. The only arm of the UN which I still fully support, and with which I have not yet become disenchanted is UNICEF.

Which is why I prefer to end on one of my favourite realizations at the museum of the ICRC – that art and beauty will always find their way, even in the most brutal and violent of realities. As example, the following was made in 1999 by Lebanese prisoners of war in Israel.

Throughout the museum, as though intentionally to provide relief and pause for the visitor, are pieces of gorgeous art created by prisoners of war (and of society, as per the temporary exhibit). No matter where we find ourselves, creativity and creation remain where our hearts find ease.

Throughout the museum, as though intentionally to provide relief and pause for the visitor, are pieces of gorgeous art created by prisoners of war (and of society, as per the temporary exhibit). No matter where we find ourselves, creativity and creation remain where our hearts find ease.

Today, I am grateful for:

1. That the POWs in my own Palestinian family are limited to two; my beloved grandfather who refused to discuss the nine months he was a prisoner, and a matrilineal uncle who went into an Israeli prison as a healthy young teenager and walked out with epilepsy because the Israelis found great fun in beating his head. (A light unto all nations…wink wink.)

2. That the maiming of my Palestinian family members is limited to one (but only because I am not counting my uncle above, nor am I including the psychological damage done to my entire family who resides in the Occupied Territories). My uncle’s wife – the uncle whom I saw in Cairo and into whose arms I fell sobbing and incapable of breathing. During one of Israel’s assaults on Gaza, she went into their room to try to sleep. Israel bombed our home, taking out one side, including the bedroom in which she was sleeping; she lost her leg.

3. The safety of my life in Canada. The safety of my travels all over this world. My blood, Faith, and nationality should not see me so safe.

Geneva | March 14, 2019

Comments closed.

Recent Comments